Deena & Meira’s Misadventure

1st Story by Meira Leonard

The most complicated flying decision I’ve ever had to face. Granted I’ve only been a pilot for less than a year so it is not saying much, but I sure hope I don’t find myself in anything remotely similar.

I moved to Oahu only a few months after receiving my pilots license back in July of last year and my new found confidence went out the window the moment I had to navigate a Class B airport as a newbie GA pilot. It took me several months to feel only slightly confident that I wasn’t going to violate airspace or at minimum sound like an idiot while sharing the radio with a 777. In addition there is a different level of respect I have for flying between islands, the vast open sea all around you, knowing that the abundant farm fields I had been familiar with back at my home airport of Galt were just not there. Ditching, though survivable, it still not an experience I wished to have.

I very much wanted to have more experience before Deena arrived so I could show her around the islands without any worries. Deena got her pilots licenses only a few months before me and we became friends while studying for our check rides together back at Galt. I was very happy that she was coming to Hawaii and that we’d get a chance to fly together.

Pressure is a funny thing. It can be seen, but often times is unseen. It can come from within yourself as well as from others. Pressure can be good and propel you towards goals or fears you’d never have faced, or bad and tangle you up into insurmountable and even dangerous situations.

The trip started out with some pressure, benign but there none-the-less. Deena and I were going to fly from Oahu to the Big Island together and I would do work remotely while she attended her medical conference, and in the afternoons we would explore the island together. In preparation, I saw that the weather leaving on Sunday looked great, but there were thunderstorms predicted during our stay which made for an unpredictable return date. A rather large miscommunication error happened at the flight school where I was renting the aircraft and I was told that it was ok to bring back the plane at a later day if needed. So Deena and I took to the skies and had a beautiful flight and even spotted many whales on our trip. I have to say I was very proud in how well I had done as I had been a bit nervous. All is well in paradise… well almost.

When we finally reached our hotel, unpacked, sat down on the sand, that’s when I got the call. The miscommunication had unraveled, instructors were upset, and it was NOT ok for me to have the plane for longer. I needed to get the plane back Tuesday afternoon if at all possible. Pressure was building… and rather strongly. I felt bad for Deena, as I didn’t want this to impact her vacation and I felt somehow responsible for the miscommunication.

Monday

Monday

Deena and I took in as much of the Big Island as we could, knowing that I might be flying back the next day. We hiked, we swam, we drove and drove some more, and ending the evening watching the red glow build from the active volcano. It was awesome and perfect.

Tuesday

I began looking at the weather to see how reasonable it was to return. The storm hadn’t fully reached the islands yet, so it looked like there would be a possibility of getting out in time. All the islands showed VFR, but Honolulu, my arriving airport showed MVFR, with OC at 2,500, scattered at 3,500, and broken at 4,500. It was a tight squeeze getting back into a rather complicated Class B airport and I knew it was just above my skill level. Good Pressure… Bad Pressure? I didn’t feel confident so I called an instructor at the flight school on Honolulu to get his thoughts. He agreed it was low, but said it would probably burn off. We waited a few hours, talked again, it hadn’t changed much so I made the call to not go. This was hard to do, as I knew the window was closing and the storm was arriving soon, which meant it would be at least a few days before I could come back. Not to mention the owner of the school was a client of mine and I felt like I was now at risk of loose his business. It got worse. The pressure as well as the miscommunications with the flight school were growing more and more, putting me in a place where now I felt judged and even blamed. It was far less than ideal.

Deena and I were a team. I have to hand it to her. Instead of this being a horrible vacation, it was a mission to accomplish. She was in it with me every step of the way and never let on that it was in any way a disruption to what should have been a relaxing vacation. I was so grateful yet I couldn’t help feeling like it was my fault and I just wished it would get resolved quickly. Pressure makes you impatient and impatience should be an immediate disqualification from being allowed to fly.

Wednesday

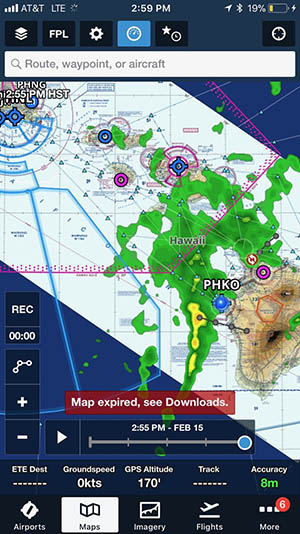

Deena and I were tracking ForeFlight like it was as heart rate monitor. I’m sure she was also trying to relieve my stress and we were again hoping for some small window in the weather to make it back home. We didn’t see one. We decided to go to the airport to at least gas up and be fully prepared for a very early flight the next morning as the weather was predicted to be clear by then.

Thursday

Up early looking at weather, out by 6:30am, returned the car, pre-flighted, and ready on the tarmac by 7:30am. Go or No go? Though there were clouds and rain, it was VFR at both arriving and departing airports but low IFR in route. Looking at the radar in ForeFlight I thought the clouds were all low and so we could fly high and land safely in HNL. It seemed like a solid plan, and I felt confident. Both Deena and I looked at each other knowing that there was still risk involved, but our drive to get home was also there. Fortunately, a Piper pilot rolled in moments later, a God moment I’d say, and we decided to get a PIREP from him. “Absolutely, 100% an IFR day ladies. I would definitely not go unless you were Instrument rated. Cloud ceilings are at 9,000”. Well that took care of that. We were grounded. Grounded but with nowhere to go. No car, no hotel, so we decided to hang out to see if the weather would pass. We wore down both our iPads and iPhones and spent almost 8 hours sitting in our plane as there was no indoor spaces available at the airport unless you had a ticket. On again and off again, we kept trying to see windows of opportunity where there weren’t any. There wasn’t much time left in the day. Both Deena and I were at our limits. Deena was also feeling sick and at this point looked miserable. I can’t describe just how much pressure I felt at this point… much like a pressure cooker. Oh and I forgot to mention, it happens that this weekend was the busiest weekend of the year on the Big Island and every single hotel room was sold out. So if we did not fly home now, we might be camping out in the plane.

‘I’ve got to get out of here’. I took a walk in the drizzly weather to clear my head. After a while, I asked myself… ‘Ok Meira, lets just say this is an ordinary day and you were thinking of taking a trip to the Big Island. Would you go?…. Hell No!’ Ok, that settled that. I came back to the plane and told Deena. We also thought about our friends and teachers back at Galt and what they would tell us… and it was unanimous… absolutely NO.

So we ended up renting one of the last cars on the island for $200, sleeping in it not more than 100 yards from where we rented it, charging our devices, and got ready for the next morning. Luckily I slept well enough to not have fatigue as yet another deterrent to fly, and we were on the tarmac and taking off by 7am. The water was placid and calm, the clouds puffy and it couldn’t have been a more serene and beautiful flight home. But arriving was much more enjoyable than I had ever imagined. It was over, and the pressure was gone. Thank God.

I will always remember this experience, in both what I learned as well as what I came to realize I hadn’t learned well enough. The uncertainty of weather, the need to follow my own knowing, and the urge to get my instrument rating. Most of all it taught me how grateful I am for pilots that have gone before us who instruct us about the danger of pressure and we are all the wiser pilots for it.

2nd Story by Deena Schwartz

Some wise pilot once said…

“Better to be on the ground wishing you were in the air… than in the air wishing you were on the ground”.

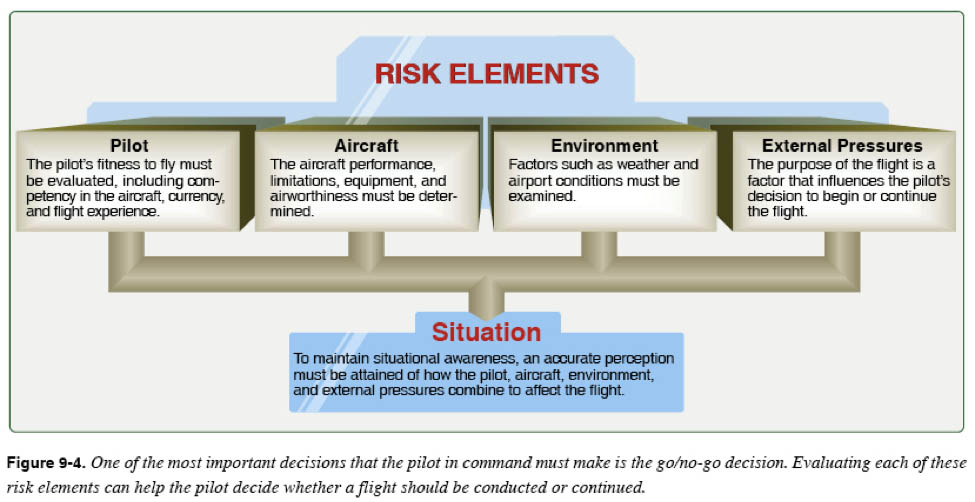

I heard those words of truth many times during my pilot training. We are all familiar with these old adages, the use of aviation mnemonics and checklists. They are an essential tool for clearly identifying hazards in order to mitigate risk. They are strategies designed and used in the aviation community as a whole and are intended to be used before each flight. I found myself thinking about and relying on these tools nearly every day of my recent trip to Hawaii. One particular checklist that remained in the forefront of my mind was PAVE. I used this nearly every day that week and it most certainly kept me calm on the ground instead of nervous in the air.

I was in Hawaii in February this year, attending an anesthesia conference and visiting my friend and fellow new pilot, Meira. Meira moved to Oahu shortly after we each passed our private pilot check rides last year and I made a point to visit her with this year’s winter escape/medical conference. The plan was to fly from Honolulu to Kona on the Big Island where my conference was being held.

All of us are familiar with the use of the PAVE checklist for individual flight risk management. Interestingly, in healthcare, specifically anesthesia, we have modeled the Aviation use of checklists in the development of our own. They are used in every area, from standards of care to managing emergency situations. In fact, my anesthesia machine’s “morning check” is very similar to PAVE and my “pre-flight check”. During one of my meetings, one of the speakers kept referencing anesthesia algorithms and checklists and the importance/utility of following them as strictly as they are followed by the aviation community. At the end of the lecture, I approached him and asked if he was a pilot. His reaction surprised me because he answered “No” as if to say, “I would never do that, it’s too risky”. Considering what we do every day, I found his reaction interesting.

In Healthcare as in Aviation, accidents happen because one does not identify risks and is caught off-guard by something that could have been anticipated. One of the most important concepts that safe practitioner of a craft understands is the difference between what is the “legal” thing to do versus the “right” thing to do.

According to the FAA, 80% of all accidents are due to pilot error. The FAA recognizes that pilots with the same certification might have different levels of experience and comfort, and even though they have the same rights to fly, they should have different personal minimum standards. “With the PAVE checklist, pilots have a simple way to remember each category to examine for risk prior to each flight. Once a pilot identifies the risks of a flight, he or she needs to decide whether the risk or combination of risks can be managed safely and successfully. If not, make the decision to cancel the flight. If the pilot decides to continue with the flight, he or she should develop strategies to mitigate the risks. One way a pilot can control the risks is to set personal minimums for items in each risk category. These are limits unique to that individual pilot’s current level of experience and proficiency.” (from AVStop.com, Risk Management)

P = Pilot in Command (PIC)

This is at the beginning of the checklist because if you are not fit to fly, then the rest of the checklist does not apply. Meira and I are new, VFR only, pilots. Inexperienced and just starting to work on IFR training. Neither of us was night current at the time. We had a well thought out plan for this trip and were feeling pretty good.

A = Aircraft

The Cessna 172 was suitable for the flight. Meira was current and familiar with that particular plane. It was equipped with life vests, a life raft and a bag of survival items like a mirror, flashlight and knife. Over the ocean, a method to collect rain water is ideal. The aircraft equipment was adequate and operational. We each had our iPads with ForeFlight and backup battery packs. Weight and balance was good for the baggage we were bringing and we had plenty of fuel reserve for the duration of the trip. A limitation was the service ceiling of the plane. We would likely not be able to climb above weather that was above 9000 feet. We were anticipating weather during the week.

V = EnVironment

For my visit, weather would be questionable for the various islands over the next few days. Thursday was going to be the earliest day we’d be able to fly out of Kona, but most likely weather would be clear on Friday throughout the islands. Weather is one of the largest risks to flying that there is. It is a major environmental consideration. Personal minimums for weather should be set and not broken. Weather in addition to terrain, Notams, TFRs, and unfamiliar airports and areas place a heavy burden on pre-flight planning and judgement. Always have a back-up plan.

Meira and I are not instrument rated yet and we found ourselves stuck in Kona on Thursday unable to leave in IFR conditions. Though an instrument rating will eventually save us in ways that I don’t even know yet, I know that the rating itself would not have helped us on Thursday. The winds were too strong and the weather was changing very quickly. Plus, we were having trouble getting reliable information about the weather in the more remote areas over the ocean between Kona and Honolulu. I wonder actually if the rating would have emboldened us to make that flight. At one point, while sitting and waiting for the weather to break we talked about what it would be like to fly in MFR conditions.

This is where the subject of external pressures comes in…

E = External Pressures

Meira had gotten a phone call from the owner of the flight school Sunday, the day we arrived in Kona. He wanted the plane back on Tuesday. But she and I both knew that the weather wasn’t going to allow that to happen. Tuesday became Wednesday and instructors were upset and had to cancel with students. Meira was firm in saying “it’s a No-go” to the owner, but I knew her guts were in knots. I’ve had similar “No-go” situations for surgeries that I’ve cancelled. No one is ever happy and it’s hard to not feel judged. The difference for me in this situation was that the burden of this decision did not fall on me. Though I completely agreed with her, it was Meira’s decision to make and I understood the weight of that. I felt badly though because this was putting her in a bad position. I was going to be leaving soon but this was her home airport now and I felt terribly that my visit put her in this position.

External pressures are influences external to the flight that create a sense of pressure to complete a flight—often at the expense of safety. Factors that can be external pressures include the following:

The management of external pressure is the single most important key to risk management because it is the one risk factor category that can cause a pilot to ignore all of the other risk factors. External pressures put time-related pressure on the pilot and figure into a majority of accidents.

I have a much deeper respect for the PAVE checklist because I was actually feeling the external pressure and was aware that is was affecting my assessment of the other risks. Being unable to meet an expectation doesn’t feel great, for oneself or for others, but the hardest part of being a pilot is not about getting the plane up in the air. The hardest part is making the right decisions in a less than ideal situation. Risks present themselves in many forms. Often times they’re not black and white. Learning to recognize and handle risks when you are in that grey zone is the key to successful outcomes. That kind of learning and confidence comes with experience, but with or without experience, checklists help immensely. Having the opportunity to really use them, I now know why some wise old pilots created them.

“There are old pilots and there are bold pilots but there are no old bold pilots.” – E. Hamilton Lee